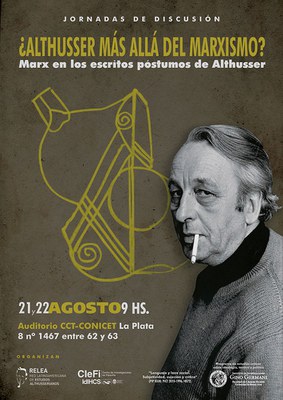

Workshop: Althusser beyond Marxism? Marx in Althusser’s Posthumous Writings

UNLP, 21-22 de Agosto, 2018

UNLP, August 21-22, 2018

Venue:

Auditorio CCT-CONICET La Plata

8 nº 1467 entre 62 y 63

Organized by:

- ReLEA- Red Latinoamericana de Estudios Althusserianos

- CieFi (Centro de investigaciones en filosofía, FaHCE-UNLP-IdIHCS)

- Proyecto “Lenguaje y lazo social. Subjetividad, sujeción y crítica” (PIP 0330, PICT 2015-1996, H872)

- Programa de Estudios Críticos sobre Ideología, Técnica y Política Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani, UBA

Since the 1992 publication of Althusser’s autobiography The Future Lasts a Long Time, nearly twenty volumes of his previously unpublished work have been released, appearing at an impressive rate. They include completed or nearly completed books that their author chose not to send to the printer’s for one reason or another, as well as articles that went unpublished or have become hard to find, some of them originally released in languages other than French; texts of lectures, classes and courses; correspondence in a variety of registers; and also directly political interventions. In all, more than six thousand pages of such material have seen the light to date. The most recent posthumous publications appeared earlier this year. Another will appear this fall, and there is reason to hope that we will see more in the years ahead. Six thousand pages is more than the Algerian-French philosopher issued in his lifetime. Like the published œuvre, this material covers a broad range of subjects; and, no less than the published œuvre, it has become the object of an extraordinary polemic that shows no signs of abating.

This enormous editorial effort, by various hands, has been underway for better than twenty-five years now. It has proceeded at a fairly steady pace in certain periods. It has, however, also been subject to the ups and downs of the French as well as the international political and theoretical conjuncture.

To begin with, this editorial endeavor has gone on in the most turbulent zones of the ideological reconfiguration of contemporary thought. But that is not all: it must also be borne in mind that the theoretical and ideological reconfiguration of the 1980s, that is, the drift toward thinking of a juridical cast (observable in Marxism as well), has made the virulent rejection of Althusserian thought one of its battle cries. Any connection to Althusser’s “theoretical anti-humanism,” taken to be a synonym for dogmatism and totalitarianism, is now anathema.

In this context, the first posthumous texts to appear offered, at a minimum, the resistance of their singularity: they could not be forced as easily as some would have liked into the mold of a caricatural structuralism considered to have been refuted in advance. This singularity crystallized in a reading in terms of “aleatory materialism” or “the materialism of the encounter,” a category embracing positions that, albeit diverse, all seemed to set out from Tony Negri’s 1993 pronunciamiento that Althusser’s posthumous writings attested a turn, a new direction, a Kehre in his thinking. On this reading, the master of the rue d’Ulm had abandoned his Marxist commitments and ventured into new theoretical waters.

These two lines of thought collided, in their turn, with a third, which emerged in the wake of the 1991 creation of the “Fonds Althusser” at the IMEC (Institut Memoires de l’Édition contemporaine) in Caen, France. This archival fonds made fifty thousand posthumous pages of Althusser’s available to the public (the twenty or so volumes we began by mentioning were extracted from this material, which was rapidly and very competently cataloged by François Matheron, with Sandrine Samson’s assistance). A number of scholars were soon hard at work on this archival material; their research spawned interpretations and questions that came into general circulation, producing a variety of effects. Matheron’s own work on Althusser, Warren Montag’s remarkable analysis of Althusser’s theoretical intervention in the French theoretical conjuncture of the 1960s, and the appearance, in our part of the world, of Emilio de Ípola’s Althusser, el infinito adiós, all testify to this development.

A third moment, one that cannot be considered a separate current both because it overlaps in various ways with the other two and, above all, because it lacks unity, emerged thanks to the importance of the pages we are commenting on here, which made it possible to recontextualize certain key aspects of the interpretations we have briefly discussed by locating them in the broader context from which they emerged. The upshot was a set of new questions, many of which revolved around Marx’s presence, and the specific nature of that presence, in Althusser’s posthumous writings. This, it should clearly be said, came down to posing the problem of Althusser’s relation to Marx throughout his work. Today, in 2018, Althusser’s centenary and the bicentenary of the philosopher from Trier, we have at our disposal, thanks to both this intense polemic bearing on fundamental features of Althusser’s thought as well as the immense editorial effort just evoked, a set of invaluable tools with which to examine the Althusser-Marx relationship. This suggests that we should readjust our portraits of both thinkers in a perspective that is, we believe, particularly favorable to such revaluation.

We would like to put forward a thesis that might serve as a starting point for discussion at this Conference. Picking up on a remark of G. M. Goshgarian’s, editor of four of the most recently published volumes of Althusser’s posthumous work, we would like to call attention to the analogy between the problem, characteristic of the “late Althusser,” of the clinamen that induces the emergence of a new world, and the problem of the “revolutionary rupture” that preoccupied the other Althussers, especially insofar as the continued existence of the world that surges up with the clinamen depends, as is the case for revolution as well, on what happens afterwards, that is, on whether a post-revolutionary society is able to reproduce itself. The attempt to think the conditions of possibility for the reproduction of a given social order is inseparable from the attempt to think this order itself.

It so happens that these conditions have been given a name: “class dictatorship” or “class domination.” To speak of the “dictatorship or domination of a social class,” consequently, is not to speak of forms in which power is exercised by that class’s representatives in what would, from a sociological perspective be conceptualized as the “juridical-political sphere”. These forms of domination cannot be ranged with political-legal forms; rather, they underpin these political-legal forms, as their condition of possibility. In the case of disciplinary power, Michel Foucault has shown how these forms of “sub-power” subtend the political-legal forms as their condition of possibility. In question here is what comes about when Marx declares that, in view of the underdetermination, from a legal standpoint, of the length of the working-day (given workers’ and capitalists’ equally rightful claims and contradictory interests), “between equal rights force (Gewalt) decides.” The dictatorship of the bourgeoisie is not reducible to its political forms, which in our time have become, in the main, parliamentary and democratic, something that is today being rediscovered with the help of expressions such as “democradura” [a Spanish portmanteau word that combines the words for “democracy,” democracia, and “dictatorship,” and dictadura]. Bourgeois dictatorship runs from the harshest forms of economic exploitation to forms of ideological pressure and blackmail both crude and subtle, combined with out-and-out gangsterism; when the need arises, it takes forms that include the massive disappearance of individuals.

If the existence of a social order comes down to the existence of its conditions of reproduction, thinking those conditions is a crucial political and scientific task. It means reflecting in a politically realistic way, that is, “not telling oneself stories” about the domination of the bourgeois class, while also thinking the conditions of the “domination of the proletarian class and its allies,” something that, in the Marxist tradition, bears the rather awkward name “dictatorship of the proletariat”: a class domination exercised by way of a political form that Marx and Lenin call “social democracy” or “mass democracy,” without being reducible to them, since it manifests itself as class domination in economic production and in ideology too. “Not telling oneself stories,” then, implies that the Latin-American Left’s protracted lament about the fact that it dared to question “formal democracy” should come to an end, and that its starry-eyed illusions about juridical ideological forms should be jettisoned as well. Above all, there should be no mistake about the fact that this is not an end point, but is the point at which history commences or recommences.

One of the basic strands in the fabric of Althusser’s posthumous writings is an intense consideration of the relationship between philosophy and the other practices. It seems to us that a profound reflection on the character sui generis of the domination of the proletariat and its allies finds its focus here, cast as a problem: how to bring about popular hegemony. For Althusser’s thinking reveals that the forms of class domination or dictatorship are entirely bound up with the forms of ideological domination. Class dictatorship is exercised by way of ideological unification, among other things, and this unification is a driving force behind class domination. Ideological unification, in turn, constitutes exploitation of the different practices, in the sense that it harnesses them to objectives beyond their scope or their specific effects. Althusser discerned – we find, in the posthumous writings, extremely insightful discussions of this point – the relationship between traditional philosophy and this task of ideological unification. In the context of Althusser’s intellectual development overall, this can be considered his way of confronting a crucial question, which he had already formulated by the late 1950s: How can one escape philosophy without founding a philosophy? His early antiphilosophical position, followed by his theoreticist position (the idea that Marxist philosophy was a science) and his subsequent promotion of “a new practice of philosophy are successive answers to this problem.

We would like to put this preoccupation with philosophy in the framework of a preoccupation with politics. Indeed, if dominant philosophies constitute the highest form of the process of unification on which the viability of a concrete social world depends, then the question of philosophy is crucial when it comes to the possibility of bringing about an alternative social order, the domination of the working class and its allies, popular hegemony. At stake are the conditions of the new social order’s emergence and viability. Concentrated in the problem of philosophy is a set of political – we might even say “ethical-political” – difficulties connected with the process of building a new form of society. Althusser ultimately arrived at the view that the absence of a Marxist philosophy one hundred years after the publication of Marx’s Capital was not just a deficiency, but a theoretical and political symptom. For the philosophy needed to help build popular hegemony cannot, he concluded, be an alternative form of unification, hence of exploitation of the different practices. Rather, it has to be their non-exploitation, a form of liberation from the onerous ideological constructs that weigh on those practices.

Undeniably, a formidable set of questions about these developments surges up here: to begin with, the question as to how far they can be faithfully or productively reconstructed, and as to the way in which these ideas of Althusser’s, forged in the heat of a crucial moment in the history of the class struggle, the mid-1970s, can be taken up again now, in a very different conjuncture, in which capitalism is being reproduced as “neoliberalism” and is, consequently, transforming all the interlinked ideological and repressive state apparatuses by means of which the dictatorship of the bourgeois class is ensured in our day. One question in particular insistently claims our attention: To what extent can the remains of the state apparatus with which capitalism once reproduced itself as a “welfare state” – obviously obstacles from the standpoint of the neoliberal offensive – contribute, in the present conjuncture, to producing effects opposed to those produced by the dominant state machinery? We also need to examine, in connection with this new practice of philosophy and the constitution of popular hegemony, the question as to which forms differ from simple “grass-roots-ism” or “autonomism,” and how such forms can be reconciled with a scientific knowledge of history. That, obviously, means that we must take a political stand. Involved here, in any case, are open questions, interrogations that we would like to define and explore: they emerge from the relationship, as precise as it is hard to describe, between Althusser’s posthumous writings and Marx’s theoretical production – and thus presuppose a definition of Marx’s presence in Althusser’s theoretical production as a whole.